Between Life and Death

In my writings I have often tried to focus on the logical application of our Torah to current events and

modern issues. However, on occasion events transpire that force us to question our paradigm – even

if that paradigm, is one generally inclined towards rationalism, it is possible to come to another other

conclusion of a mystical/spiritualist existence that is less rational.

We landed on the 16 th of May in the Philippines after an intense 15-hour journey from the UK with a heavily pregnant wife, 3 small children and a brief transfer in Abu Dhabi. We arrived jetlagged,

hungry and utterly exhausted.

The fatigue was intense. I was suddenly in a new country I had never visited and interacting with a

new community whom I had never met. Despite this, I ran my first prayer service at the Jewish

Association of the Philippines and prepared myself to perform a funeral for an individual I had never

met.

I rode to the cemetery with some members of the board of the Synagogue and other members who

had joined to make the necessary Minyan of ten men required for these prayers. As we passed

through Manila I took in the stark contrast of wealth and poverty that exist simultaneously in the

Philippines and fought through the jetlag as I answered Halachic (legal) and Hashgophic (general or

non-legal) questions as well as meeting and greeting people for the first time.

As we drove through the Manila traffic towards the Jewish cemetery one congregant began to share

with me that the northern cemetery of Manila is home to some 6 000 people (approximately 800

families) who live amongst the graves in a developed community that has existed from the late

1950’s – to see examples of this in person was moving and powerful and I was immediately humbled

and profoundly moved by what I saw.

Suddenly, as we walked through the winding cemetery with its different sections, my phone with its

new sim card began to ring. It was my father calling which at 10.30 in the morning Philippines time

could only be extremely early morning or late night in the UK (depending on perspective!).

He sounded as tired as I was.

My father told me that my uncle Kurt had been moved back to hospital and that his health was

failing due to leukaemia and complications caused by diabetes. More recently he had several falls

and needed medical assistance. It was with a deep sense of guilt that I explained to my father that I

was not able to speak, and we scheduled a time to catch up later in the day.

My uncle Kurt had always been a small but powerful hero in my life. I remember with fond

memories my uncle Kurt picking me up from school in his London black cab, his infectious roaring

laugh and seemingly encyclopaedic knowledge of jokes, puns and funny stories he would share to

amuse me.

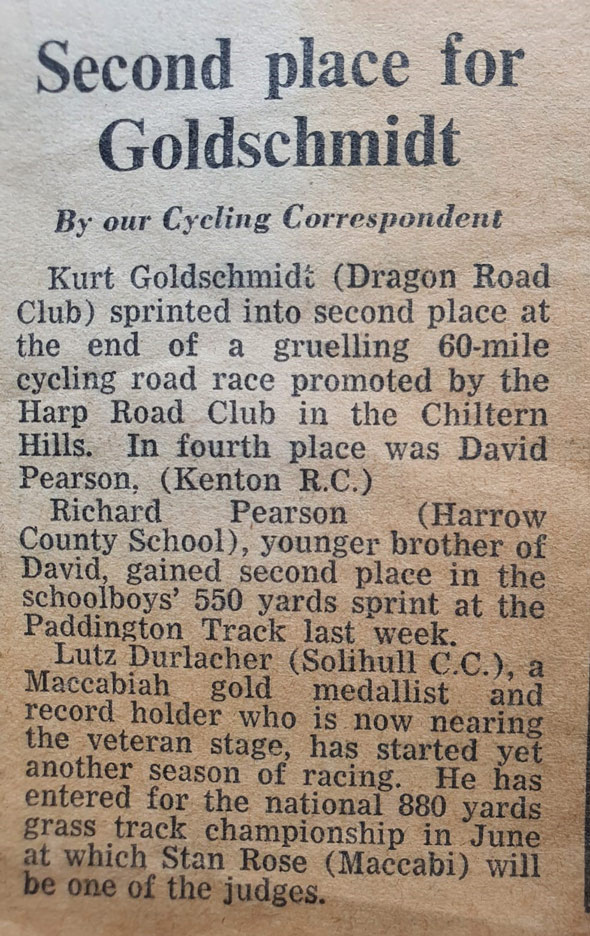

Kurt was an avid follower of all kinds of sport and his main interest was cycling. He had competed

professionally and as a contestant in the Maccabee Games:

I remember that simultaneously he was a deeply private person and his jolly and jovial attitude

starkly contrasted against his past as some of the youngest passengers on the kinder-transport:

along with his identical twin brother he had been smuggled out from Austria/Czechoslovakia during

the Holocaust, placed into social care in England and then reunited with their father, my

grandfather, after he had arrived in England some years later – these were all details that my father

and I had discussed many times. Kurt and Bert had been blessed and saved from the destruction that

stormed through Europe sparing so few and losing so many, including the lives of their mother,

brother and maternal grandmother.

The temperature in the cemetery was a humid 31oC that, having been at 9oC only yesterday in

London seemed as intense as an oven. We walked through the graves and met those who called it

home, moving the coffin together as a community.

I knew virtually nothing about the deceased and so I quickly introduced myself to his family and

partner and heard a little about the man, his work and interests. Quickly I prepared something to say

and looked up the relevant prayers from the Siddur. Following this we laid him to rest, assisted by

those who live there amongst the graves in the main cemetery.

As we concluded the service, a member of the board turned to me and in a very friendly manner

said, “Rabbi, did you know that there is a grave here with the name Goldschmidt?!”

In a strange dreamlike way, we collectively followed him through the winding paths and past the fragrant frangipani trees down towards the back of the plot. As we reached the grave a chill ran through me,

and I totally forgot the sweltering heat.

There before me was the grave of Kurt Goldschmidt.

Eventually, they explained that there was little information on the older graves and that many of

these older graves did not have accessible records.

My wife and I debated telling my father the story and I waited until we spoke after Shabbat to tell

him the tale and await his reaction. I was unsure how exactly to share it with him, the seriousness of

Kurt’s health decline made me reconsider – perhaps this was insensitive given the gravity of the

Situation:

“Dad, can I show you something?” – I then proceeded to send him the photo of the grave via

WhatsApp and await his response. After what seemed like an eternal silence he told me that Kurt

had bounced back slightly following his hospitalisation and agreed with me that it was extremely

peculiar that after we had spoken I had chanced upon a grave with his name.

After we returned from the Philippines we began preparing for the arrival of our new baby; aside

from some travel for work and other errands I found myself distracted and unable to really focus on

writing and learning. We set about moving ourselves to Somerset, where we had birthed previously

in the calm space of my mother’s house in the village of Porlock. Both my wife and I feel strongly

about home-birthing and natural medicine, since our marriage I have helped delivered all of our

children including 2 of them without assistance. As we packed to leave my father and I visited Kurt

who was now in living and being cared for at the new Jewish Care facility.

It was difficult to see him looking so weak and vulnerable, I had always thought of him as larger than

life and with an almost impossible to break spirit. I saw immediately that he was getting truly the

best care and that gave me a great deal of solace and comfort. I explained to him that we were

preparing for the imminent birth and fed him some fruits and chatted a little. Although weakened

and occasionally drifting in and out of consciousness, he managed to crack a few jokes and interact

and understand everything I said to him. The next day we jumped on the train and made our way

down from London to the picturesque coastal area of Somerset, a place where I had spent a great

deal of my own childhood.

As Kurt’s condition became more and more terminal and we moved closer and closer to the birth,

there was some strange synchronicity: as he was hospitalised again, we immediately began the

Braxton Hicks contractions. From my perspective I was experiencing life and death simultaneously

and vicariously; neither of these experiences was happening directly to me, my uncle was miles away

and my wife waited expectantly as her body prepared for the birth. Neither was in my control or

even within my ability to experience.

The month of May began its first day with the passing of my uncle Kurt and we ended the month

with the birth of Ilan Neriah on the 27 th – during this time I reflected deeply on life and death;

the shadow of the Holocaust contrasted against the promise of new life. My hopes and fears seemed

magnified by the Covid and financial situation and between these two experiences we finished with

the Paradesi Synagogue in India and signed our new contract with the Jewish Association of the

Philippines. Life, it seemed, had not come full circle but rather had shifted and moved into a new

space.

It is rare that life and death occur so close and against the backdrop of change; both require stability

and peace for them to occur in a gentle transition. Despite this, I feel that the passing of Kurt and the

coming of Ilan were both peaceful and immensely profound experiences at different ends of

a encompassing spectrum – life itself cannot exist without either and our hopes and fears of life and

death is equally natural and inescapably human.

Rabbi Jonathan Goldschmidt 2022 ©